Dorothy Draper, The Greenbrier Decorator

“Show Me Nothing That Looks Like Gravy”

Dorothy Draper arrived by train in 1946 in White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., facing the daunting decorating task of resurrecting a stately Southern resort.

“Show Me Nothing That Looks Like Gravy”

Dorothy Draper arrived by train in 1946 in White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., facing the daunting decorating task of resurrecting a stately Southern resort.

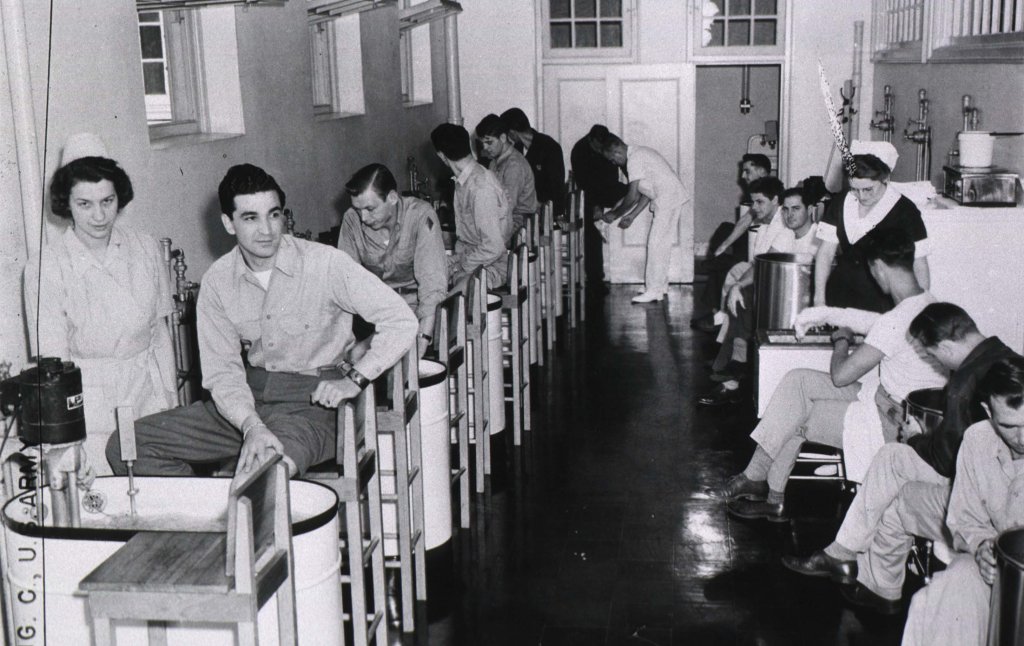

The Greenbrier had been converted to a 2,000-bed hospital by the U.S. Army during World War II, treating more than 24,000 soldiers. Draper walked into the empty hotel, wielding a flashlight to comb the corridors. She had embarked upon the largest redecoration project in the history of the American hotel industry at the time.

Sixteen months and thousands of wallpaper rolls, gallons of paint and yards of fabric later, Draper had transformed The Greenbrier resort into an eye-popping oasis. She called The Greenbrier the jewel in her crown. That is quite a statement, considering that she was lauded for many high-profile projects, including hotels in Brazil, California and Chicago, as well as a dining room in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She designed everything from jet plane interiors to The Greenbrier’s matchbook covers, menus and staff uniforms.

Draper [1889-1969] was born into a wealthy New York family. She is credited with establishing the first interior design company in the U.S.

The woman that Good Housekeeping magazine called the doyenne of decorating deployed colors as striking as her personality. “Nothing adds so much to the beauty and happiness of this world as color. Without it we droop,” Draper wrote in Entertaining is Fun! Then she urged her readers, “Now promise me that you won’t read any more until you paint your door …”

Dorothy Draper called The Greenbrier the jewel in her crown.

When her protégé, designer Carleton Varney, first went to work for her company, he was struck by her presence. “I vividly recall Mrs. Draper’s appearance,” he wrote. “Tall and imposing, head topped with a bright strawberry satin hat, full black cape, gloves, and penetrating eyes. She reminded me of a female Roman gladiator, ready to conquer all she viewed.

“Dorothy would come around and look at everyone’s station and she would say, ‘Show me nothing that looks like gravy.’ ”

The New York Times called Draper a maximalist decorator, “known for her Hollywood Regency flourishes – enormous striped, hot colors and swirls of plaster relief.”

Varney would later become president of Dorothy Draper & Co., carrying forward Draper’s vision, including The Greenbrier’s atmosphere. “Mr. Varney learned that every room needs a touch of black, and perhaps a mirrored wall,” The New York Times reported. “He learned to mix at least three or four prints and patterns per room.”

When The Greenbrier reopened after World War II with a gala in 1948, some visitors expecting traditional Southern décor were taken aback at the bright blend of patterns surrounding them as they stepped onto the checkerboard marble flooring. But Draper’s exuberant style suited a war-weary world. Celebrities flocked to see the $4.25 million renovation. Famous guests included entertainer Bing Crosby, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and such prominent families as the Astors and the Vanderbilts. Draper herself was one of the celebrities.

Draper also reached out to average homemakers, recommending such economical updates as slipcovers. She outlined in her book Decorating is Fun! the decorating principles of courage, color, balance, smart accessories and comfort, giving advice as emboldening now as it was in 1939: “You need courage to experiment, courage to seek out your own taste and express it, courage to disregard stereotyped ideas and try out your own. Don’t be in the least disturbed by trends or fashions, or anyone else’s advice. They are probably wrong. Be critical – never humble.”

Her emphasis on color was right behind courage: “I wish there were one word in the English language that meant exciting, frightfully important, irreplaceable, deeply satisfying, basic and thrilling, all at once. I need that word to tell you how much your awareness of color means to you in decorating.”

Today’s visitors to The Greenbrier delight in experiencing what has become known as the Draper touch of inviting colors, patterns and vivid contrasts.

Just as Draper encouraged her readers to embrace their inner decorator, The Greenbrier opened the Dorothy Draper Home store for those wanting to bring this refreshing style to their daily lives.

The store’s unique offerings include fabric and wallpaper with the Dorothy Draper Rhododendron print she designed for The Greenbrier’s 1948 reopening. A sample of this representation of West Virginia’s state flower is part of the Cooper Hewitt collection of the Smithsonian Design Museum.

Perhaps the average shopper won’t need quite as much Rhododendron wallpaper as Draper used at The Greenbrier – an impressive 15,000 rolls.

Experience The Greenbrier for yourself. Overnight and day visitors are welcome.

Researched and written by Belinda Anderson.

Anderson writes extensively about the histories of places and people. “The first time I visited The Greenbrier,” she remembers, “I was immediately immersed in the energy and grandeur of Dorothy’s vision. I’ve been to some grand places in the U.S., including the Hearst Castle and the Biltmore estate, but I found a special version of grand when I stepped into Dorothy’s world.”

Join the Greenbrier Valley enews, and stay connected with the latest news and happenings... with a few extra perks only for our subscribers!